Short answer: yes, ADHD can be passed down from both mom and dad. Genetics explains roughly 7080% of the risk, and there isn't a single mother-only or father-only gene that decides who gets it. Knowing this helps families move past blame, plan early screenings, and understand what the science actually says.

Why does this matter to you right now? If you've noticed attention-related challenges in a child, a sibling, or even yourself, the question Is ADHD genetic from mother or father? often pops up. Getting a clear, evidence-based answer can ease anxiety, guide conversations with doctors, and let you focus on what really matters: support, strategies, and hope.

Understanding Genetic Inheritance

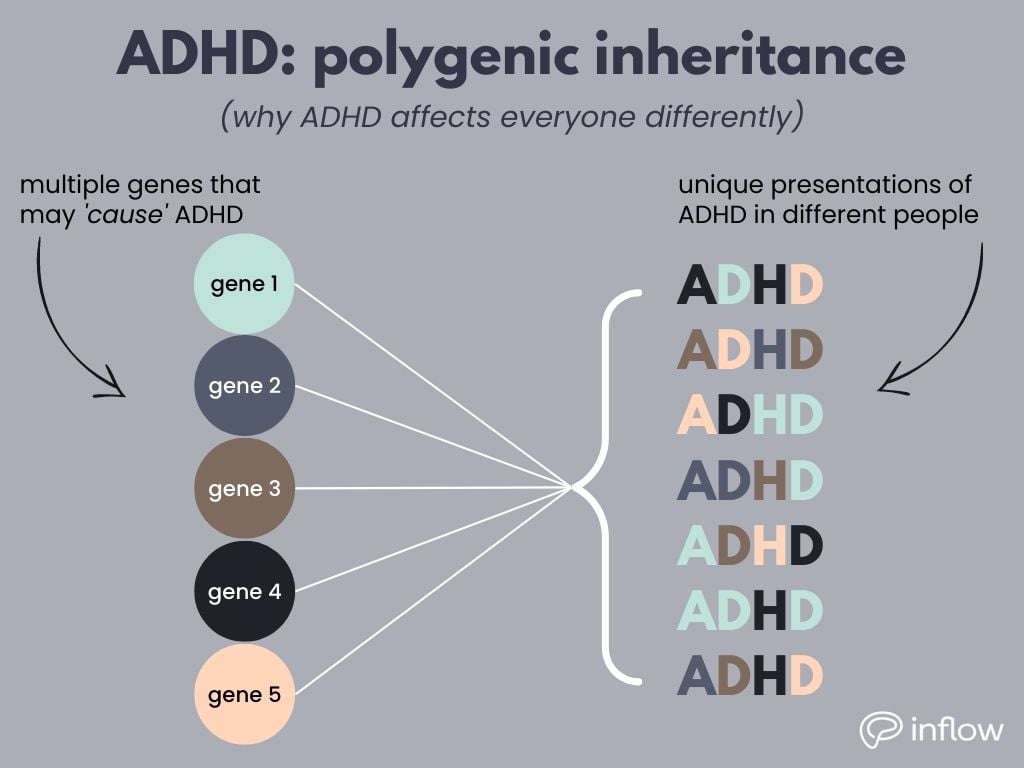

Polygenic nature of ADHD

ADHD isn't a single-gene disorder like cystic fibrosis. Instead, it's polygenicdozens, maybe hundreds, of tiny genetic variants each add a sliver of risk. Think of it like a smoothie: each fruit contributes a flavor, but no single one makes the whole drink. Researchers have identified plenty of these flavor genes through large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS). A recent study highlighted more than 200 risk loci, confirming the complex, multigene picture. If you're interested in how both genetic and environmental factors combine, you can read more in this article on ADHD environment.

Heritability percentages

When scientists talk about heritability, they're describing how much of the variation in a trait across a population can be chalked up to genetics. For ADHD, twin and family studies consistently land in the 7080% range. In plain language, if you take two identical twins, one with ADHD, the other has a high probability of showing similar symptoms, even if they've grown up in different environments. This high figure is why many parents wonder if the gene came from mom or dadthe answer is: both contribute, and the odds add up.

Nature versus nurture

Genetics sets the stage, but it's not the whole play. Environmental factors like prenatal exposure to nicotine, early childhood stress, or even the quality of school support can amplify or dampen the genetic risk. A fascinating concept called genetic nurture suggests that a parent's own genes can shape the child's environment (for example, a mother's anxiety levels influencing home stress). However, a recent study from Norway found no significant maternal effect beyond genetics. So while the environment matters, it doesn't overturn the core genetic contribution.

Mother vs Father

Equal contribution from both parents

Most large family studies show that the risk from mothers and fathers is roughly equal. A review noted that when a parent with ADHD has a child, the child's risk jumps to about 5060% regardless of whether the parent is the mother or the father. This roughly equal odds ratio suggests that the gene roulette spins the same way for both parents.

Maternal-specific studies

Some researchers have dug deeper into whether moms pass on extra risk through the womb. Prenatal exposure to substances like nicotine, alcohol, or high stress hormones can affect brain development, and those exposures are often linked to maternal health. Yet a comprehensive analysis of thousands of motherchild pairs found that while prenatal adversity raises ADHD symptoms, the underlying genetic transmission remains similar to paternal transmission. In other words, the mother's genetics matter, but there isn't a special maternal-only gene that makes ADHD more likely.

Paternal insights

Fathers bring their own set of genetic variants, and recent studies suggest that sperm DNA methylation patterns (tiny chemical tags that affect gene expression) may play a role in neurodevelopmental outcomes. One Swedish twin cohort observed that children with fathers who had ADHD were just as likely to develop the condition as those with mothers who had it. This reinforces the idea that both parental lineages matter equally.

Can ADHD skip a generation?

Because ADHD is polygenic, it can appear to skip a generation. Imagine a parent carries a handful of low-impact risk alleles that, on their own, don't trigger noticeable symptoms. When those alleles combine with another set from the other parent, the child may cross the threshold for clinical ADHD. This pattern looks like a gap in the family tree, but genetically it's just the additive effect of many small genesnot a classic dominant or recessive inheritance. Increased awareness of these patterns can also help families recognize early ADHD symptoms trauma for timely intervention.

Brain and Genetics

Neurotransmitter pathways

The most studied brain chemicals in ADHD are dopamine and norepinephrine. Many of the risk genes influence how these neurotransmitters are produced, released, or reabsorbed at synapses. For example, variations in the DAT1 gene (which codes for the dopamine transporter) can lead to slower dopamine clearance, affecting attention and impulse control. This is why stimulant medications that boost dopamine availability often work well for many patients.

Brain structure differences

Neuroimaging studies consistently show that people with ADHD have subtle differences in the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and cerebellumareas involved in executive function, attention, and motor control. Those structural nuances are partly shaped by the same genes that influence neurotransmitter pathways. In a large MRI meta-analysis, children with a higher polygenic risk score for ADHD showed reduced cortical thickness in the right inferior frontal gyrus, a hotspot for inhibitory control.

Environmental triggers

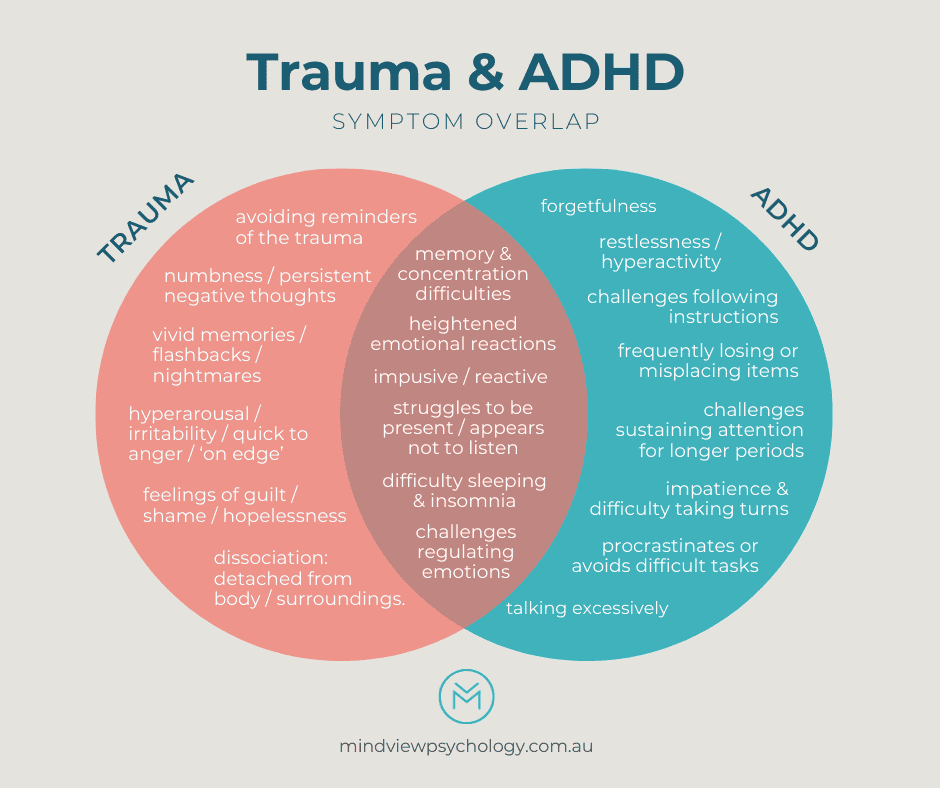

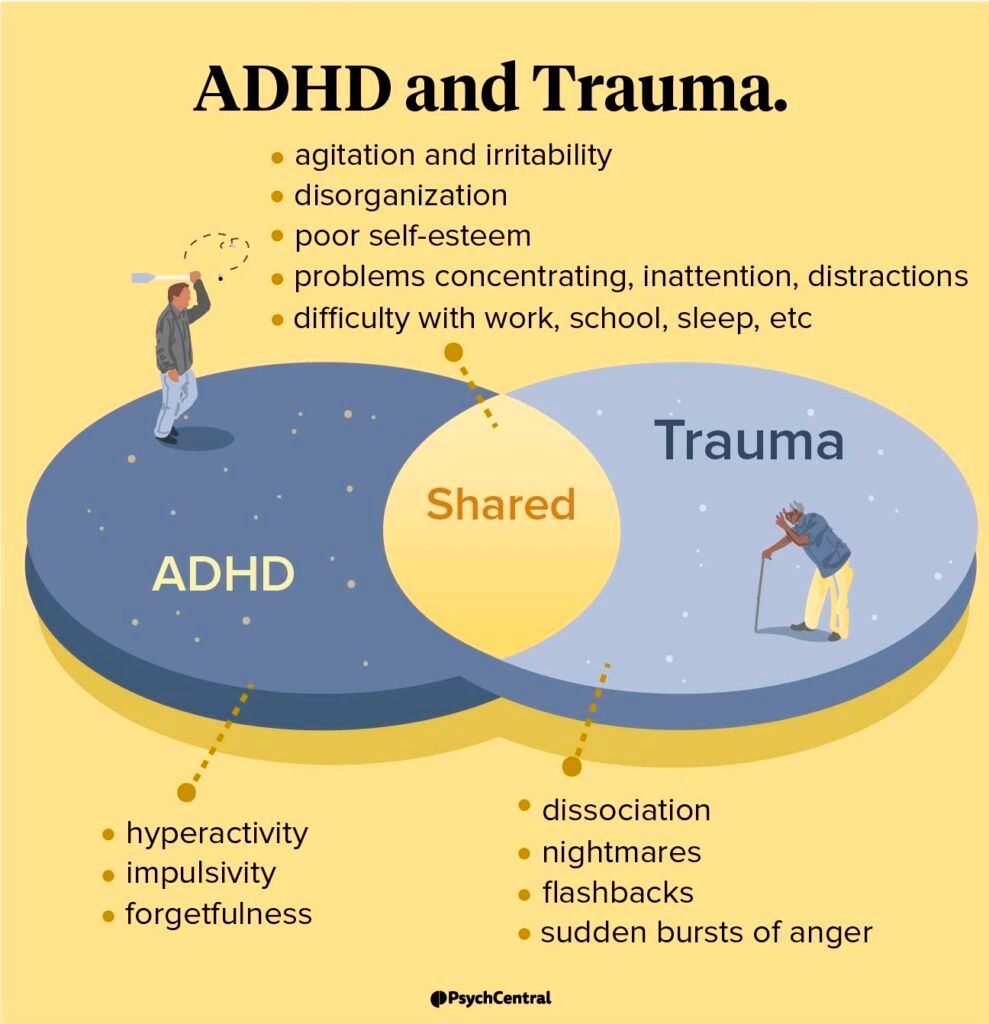

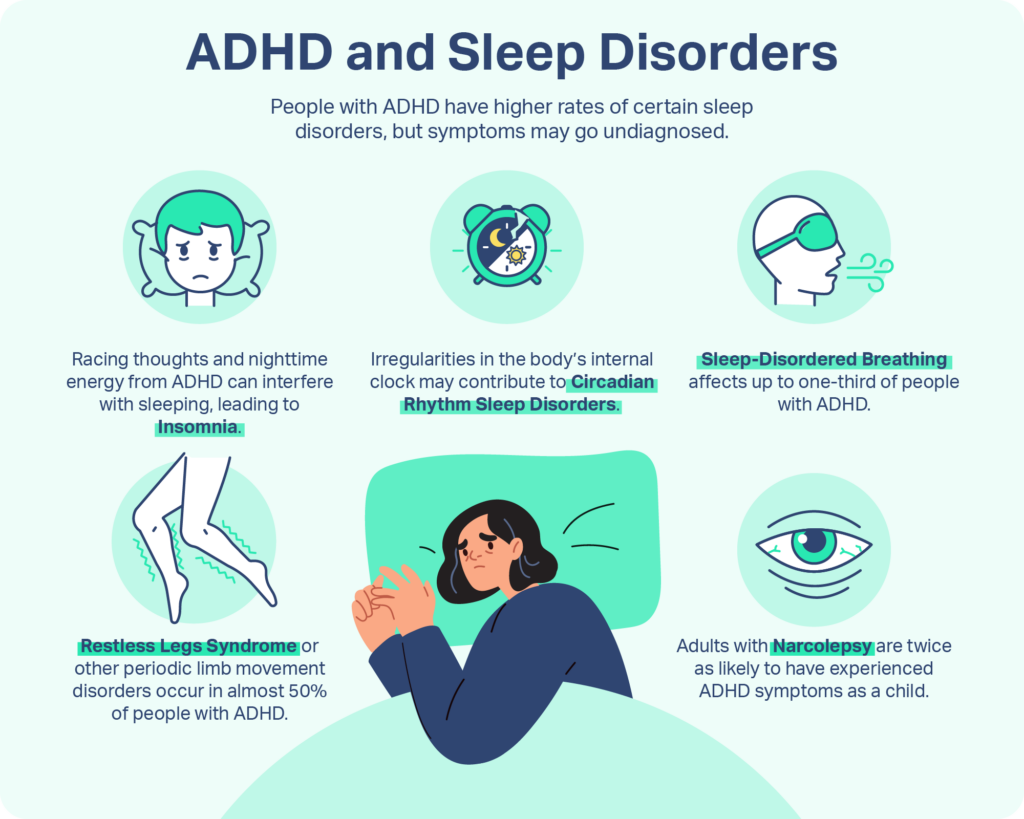

Even with a high genetic load, the environment can tip the scales. Early childhood adversity, low socioeconomic status, and exposure to lead or tobacco smoke have all been linked to increased ADHD symptoms. An article in CHADD outlines how these factors interact with genetics, creating a double-hit scenario that heightens the likelihood of a diagnosis. If adverse childhood experiences are present, understanding the childhood trauma ADHD connection is also crucial.

Family Real World Stories

Case study: parents both diagnosed

Meet Maya and Alex. Both were diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood after their teenage daughter, Lily, struggled with school. Genetic testing isn't routine for ADHD, but the family's history gave them a clue. Maya noticed that her own childhood impulsivity resurfaced when Lily started having trouble focusing. Alex, who had always been the restless one, finally saw his own patterns reflected in Lily's behavior. Together, they pursued a comprehensive evaluation, confirming Lily's diagnosis. Their story illustrates how parental ADHD can raise awareness, prompt early screening, and lead to supportive interventions for the next generation.

Personal anecdote: shifting blame

When I first learned about ADHD in my own family, the conversation was messy. My sister blamed our mother, insisting it's all her genes. I reminded her that research shows both parents contribute, and that blaming a single parent only breeds guilt. We talked about the polygenic nature, the shared environment, and the fact that many siblings in our family were fine. By reframing the discussion, we moved from finger-pointing to a shared plan: regular check-ins with a pediatrician, behavioral strategies at home, and a compassion-first approach.

Screening checklist

Whether you suspect ADHD in a child, teenager, or even an adult, a quick self-screen can guide next steps. Here's a simple checklist you can use with your family:

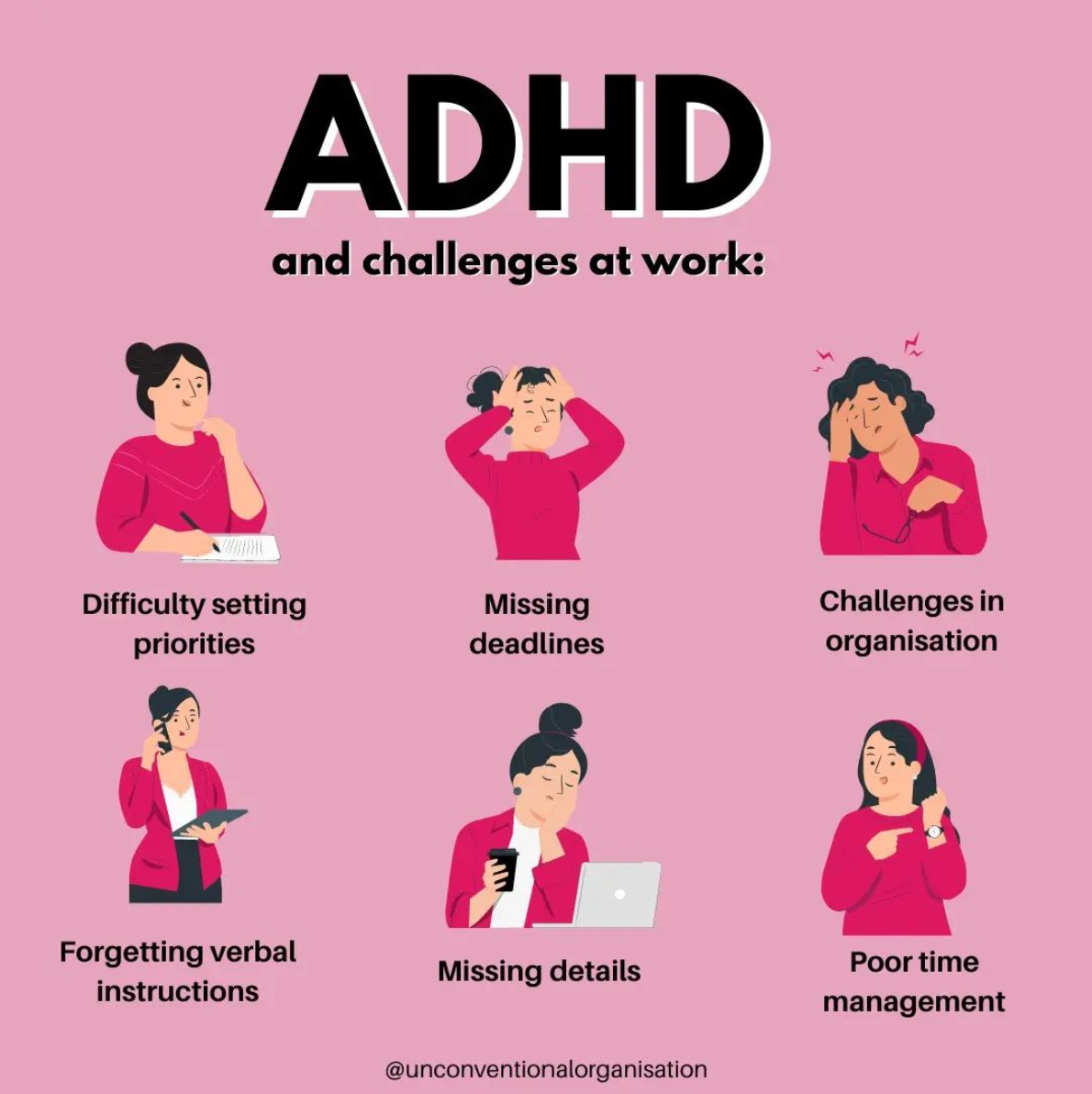

- Do you notice persistent inattention (e.g., trouble staying on task, frequent daydreaming) for at least six months?

- Is there a pattern of impulsivity (e.g., acting without thinking, interrupting others) across settings?

- Has anyone in the immediate family (parents, siblings) been diagnosed with ADHD or displayed similar traits?

- Are there any prenatal or early-life risk factors (e.g., maternal smoking, low birth weight)?

- Do symptoms interfere with school, work, or relationships?

If you tick several boxes, consider talking to a medical professional. Early identification often leads to better outcomes, especially when you have a clear picture of the family's genetic background.

Final Key Takeaways

Bottom line: ADHD is a highly heritable, polygenic condition that doesn't favor mom or dadboth parents pass on risk, and those risks can combine in ways that sometimes look like a skipped generation. Genetics provides the baseline, but brain chemistry, structural differences, and environmental influences shape the final picture. Understanding this balanced view reduces blame, encourages early screening, and empowers families to take proactive steps. If you've recognized ADHD traits in yourself or a loved one, reach out to a clinician, explore supportive strategies, and remember you're not alonescience, community, and compassion are on your side.

FAQs

Can ADHD be inherited only from one parent?

No. ADHD is polygenic, meaning risk comes from many small genetic variants contributed by both mother and father.

Does a mother’s pregnancy affect the child’s ADHD risk?

Pregnancy factors such as smoking, alcohol, or high stress can increase risk, but they act on top of the genetic risk passed by both parents.

How likely is it that a child will develop ADHD if both parents have it?

If both parents have ADHD, the child’s risk rises to roughly 60‑70 %, reflecting the additive effect of multiple inherited risk genes.

What does “polygenic” mean for ADHD inheritance?

Polygenic means many genes, each with a small effect, combine to shape the overall risk rather than a single dominant gene.

Are there any genetic tests that can predict ADHD?

Currently there are no clinical tests that can predict ADHD with certainty; risk is assessed through family history and behavioral evaluation.